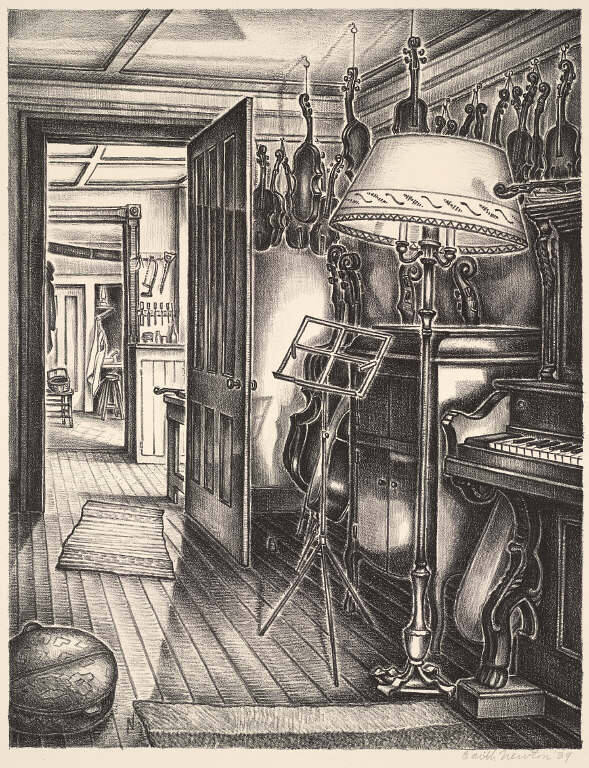

Object Details

Artist

Rembrandt van Rijn

Date

1658

Medium

Etching, engraving, and drypoint on laid paper

Dimensions

Image: 9 x 7 1/4 inches (22.9 x 18.4 cm)

Sheet: 9 1/8 x 7 5/8 inches (23.2 x 19.4 cm)

Credit Line

Acquired through the Museum Associates Purchase Fund

Object

Number

65.068

This etching from 1658 is perhaps Rembrandt’s finest print of a nude, and certainly embodies an unus(…)

This etching from 1658 is perhaps Rembrandt’s finest print of a nude, and certainly embodies an unusual and touching aspect of his treatment of this subject, a kind of shy eroticism, a chaste nakedness, overt and tentative at the same time. His other etchings in the 1650s of women in various stages of undress show them sleeping, turned away from us, or in profile, very different from the explicit and dramatic versions of this subject from more than a quarter century earlier, in the early 1630s. This radiant image is an intimate and domestic successor, as it were, to the monumental painting of Bathsheba from 1654, in the Louvre; both figures are in profile, looking down without expression, thereby gaining greatly in gravity and spiritual depth. This impression is from the final state of the print; there are two primary differences from the earlier states: the removal of the woman’s cap, and the addition of a key on the chimney of the stove. The first change allows the niche (or closed window) behind the woman’s head to reverberate around her; the second adds a tactile, down-to-earth detail to the scene that makes it more domestic and immediate. This is a beautiful, lifetime impression of one of Rembrandt’s most sensitive prints, with a remarkably subtle play of light and shadow throughout the room.

(From “A Handbook of the Collection: Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art,” 1998)

—-

Throughout the 1650s, Rembrandt made several prints of women in various states of undress. Likely springing from direct observation, these images may relate to life drawing sessions held in the master’s studio, in which artists would “draw male or female nude models from the life by warm stoves,” as one of Rembrandt’s pupils described.In addition to its pedagogical purpose, the image may also offer a moral undertone. Although women posed nude in Amsterdam artists’ studios well before the practice became commonplace elsewhere, the act of undressing for male artists was nevertheless considered scandalous. Documentary evidence indicates that many of these female models were prostitutes. Nothing is certain about the woman’s identity, but some details in this print suggest a condemnation of the act of posing nude, including the presence on the stove of a relief depicting Mary Magdalene, a saint traditionally understood as a reformed prostitute.

(“Lines of Inquiry: Learning from Rembrandt’s Etchings,” curated by Andrew C. Weislogel and presented at the Johnson Museum September 23–December 17, 2017)