Object Details

Artist

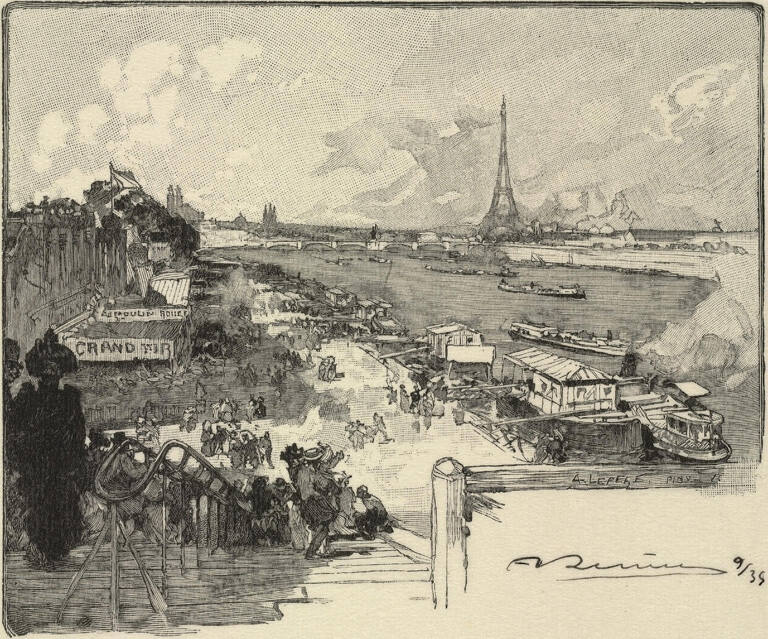

Auguste Louis Lepère

Date

1890

Medium

Wood Engraving

Dimensions

Image: 4 x 4 3/4 inches (10.2 x 12.1 cm)

Sheet: 9 1/8 × 7 3/16 inches (23.2 × 18.3 cm)

Credit Line

Gift of Charles M. Thorp, Jr.

Object

Number

64.0214

The Eiffel Tower is an icon so inextricably associated with Paris that it is impossible to envision (…)

The Eiffel Tower is an icon so inextricably associated with Paris that it is impossible to envision the city without it. These wood engravings by Auguste Lepère treat the tower, which was erected in 1889 as the entry arch to the Paris Exposition Universelle, as a new aspect of the Paris skyline. Lepère’s night view shows his fascination with the tower, seen from across the Seine; electric spotlights rake the ground from the observation platform, and the tower itself dwarfs the exposition buildings to either side. The daylight view is taken from the Viaduc du Point du Jour (also known as the Auteuil viaduct), a double-decked railroad and pedestrian bridge across the Seine completed in 1865 at what was at that point the city’s western extremity. The Eiffel Tower naturally dominates the skyline, surpassing the Palais du Trocadéro in the middle ground at left and even what appears to be the far-off Basilique du Sacré-Coeur in the background at center, which stands on Montmartre, the highest point in the city. In 1890 when Lepère made this print, the main and subsidiary domes of Sacré-Coeur were actually still under construction; he has chosen to complete them virtually, in much the same way that Giovanni Battista Falda depicted the proposed (but never completed) terzo braccio of Bernini’s colonnade in St. Peter’s square in Rome. Lèpere’s view, is, therefore, a forwardlooking view of a Paris skyline in the process of becoming, punctuated both by symbols of France’s engineering prowess and her continued religious devotion. Lepère’s blocks were published in Harper’s Monthly in June 1892, illustrating an article by Theodore Child, a travel writer and the Paris agent for the magazine. In his article, this image bears the slightly erroneous title of “View from the Pont du Jour” but accurately asserts the crucial role of the Viaduc de Pointdu- Jour in carrying the circular railway into the heart of the city and serving as a terminal for the city’s steamboats. In Child’s characteristically florid assessment of the Eiffel Tower, it is interesting to note how he expresses to his American readers the tower’s status as the city’s main landmark:

All along the river the silhouette of the Eiffel Tower, that monstrous plaything of humanity, that gigantic point of exclamation which Progress set up at the entrance of the world’s fair in the centennial year of Liberty, will pursue us. At each step we turn to it as a standard or a contrast as we advance between rows of palaces and of quays lined with luxuriant trees; past the modest glass galleries of the Palais de l’Industrie, which seemed so gorgeous when the world’s fair found sufficient room in them in 1867; past the Esplanade des Invalides and the dome that carries us back to Louis XIV.; past the embassies and ministries on the Quai d’Orsay; past the classic temple where the deputies meet to discuss and to make laws; past the place which used to be called the Place Louis XV., until one day it was called Place de la Révolution, and in 1795 Place de la Concorde, after it had been stained with the blood of Louis XVI., of Marie Antoinette, Charlotte Corday, Anacharsis Clootz, Danton, Camille Desmoulins, and how many others!

(Andrew C. Weislogel, “Mirror of the City: The Printed View in Italy and Beyond, 1450–1940,” catalogue accompanying an exhibition organized by the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, curated by Andrew C. Weislogel and Stuart M. Blumin, and presented at the Johnson Museum August 11–December 23, 2012)