Object Details

Culture

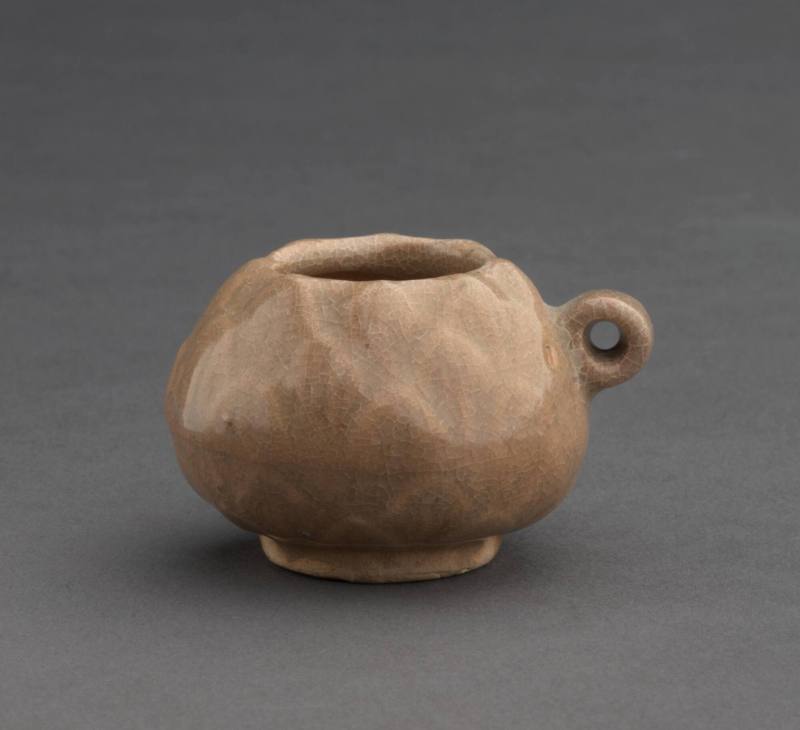

Jama-Coaque (Ecuador)

Date

300 BCE–400 CE

Medium

Earthenware

Dimensions

4 3/4 × 3 1/8 × 3 1/8 inches (12 × 8 × 8 cm)

Credit Line

Gift of Thomas Carroll, PhD 1951

Object

Number

2006.070.090

BRIEF DESCRIPTIONThis is a fragment of a Jama-Coaque ceramic figure.WHERE WAS IT MADE?This fragment (…)

BRIEF DESCRIPTIONThis is a fragment of a Jama-Coaque ceramic figure.WHERE WAS IT MADE?This fragment was once part of a figure that was made in the coastal region of what is now Ecuador.HOW WAS IT MADE?A variety of clay hand-building techniques could have been used to make the original figure. The hollow interior of this fragment bears imprints of woven cloth or fabric, suggesting that the figure was at least partially formed over some sort of textile-covered surface. To harden the clay, the figure was fired in an earthen pit.HOW WAS IT USED?The original function of archaeological figurines found in museum collections is uncertain. Today archeologists carefully record information about the associations between artifacts and the circumstances of their burial as they are unearthed, and we can draw many conclusions about object function. However, very few of the archaeological objects found in museums today were excavated in a careful, scientific manner, so we have fewer clues about their past associations and function.A wide range of people and objects are shown in pre-Columbian pottery. From burials, we know that the variety of head shapes, jewelry, and clothing styles reflect the actual appearance of these prehistoric people. Because figurines represent many life stages and ordinary human activities, they probably served to exemplify the usual norms of behavior, to serve as guidelines or rules to help socialize people and integrate them into society. Although obviously decorative, figurines could also have been used to make offerings to supernatural powers, to serve as good luck charms, or to accompany the dead as grave goods.WHY DOES IT LOOK LIKE THIS?Notice the asymmetrical headdress; it may represent cranial deformation. Manipulation of head shapes was common throughout Mesoamerica and South America in pre-Columbian times. Human head shapes can be deformed or changed in infancy, since the skull is relatively soft. Common pre-Columbian head shapes were produced by tightly circling the baby’s head with cloths (to produce an annular or tall rounded shape), or by tying boards or other hard objects to the back of the head and/or the forehead (to produce a broad, flat shape). Differences in head shape served to mark geographic origins or group affiliation. In the Andes today, hats are used in a similar way, with each community having characteristic headgear distinct from those worn in neighboring areas.To see complete Jama-Coaque figures in the Johnson Museum’s collection, search for object numbers 2006.070.080, 2006.070.083, 2006.070.087, and 2006.070.093 in the keyword search box.ABOUT THE JAMA-COAQUE CULTURE:The Jama-Coaque culture flourished in the semi-arid area between the Cabo de San Franscisco and the Bahía de Caráquez on the coast of Ecuador. The Jama-Coaque people lived in a series of small urban centers, and were organized into one or more chiefdoms, probably led by religious leaders. Their economy relied on a combination of farming and fishing. The artistic achievements of these people were of very high order; their ceramic human figures are expressive and individualized, with people often portrayed in naturalistic positions, engaged in actions and movement whose charm still resonates across the centuries. The Jama-Coaque culture shares many characteristics with the neighboring Regional Development Period (500 BC-AD 500) cultures of Bahía, Guangala, and La Tolita, all of which are local successors to the earlier, more widespread Chorrera cultural horizon.