Object Details

Culture

Ethiopia

Date

probably 19th century

Medium

Colors on goatskin

Dimensions

Approx.: 44 × 32 1/2 inches (111.8 × 82.6 cm)

Frame: 48 1/2 × 38 × 4 1/4 inches (123.2 × 96.5 × 10.8 cm)

Credit Line

Gift of Maurice W. Perreault

Object

Number

2003.074

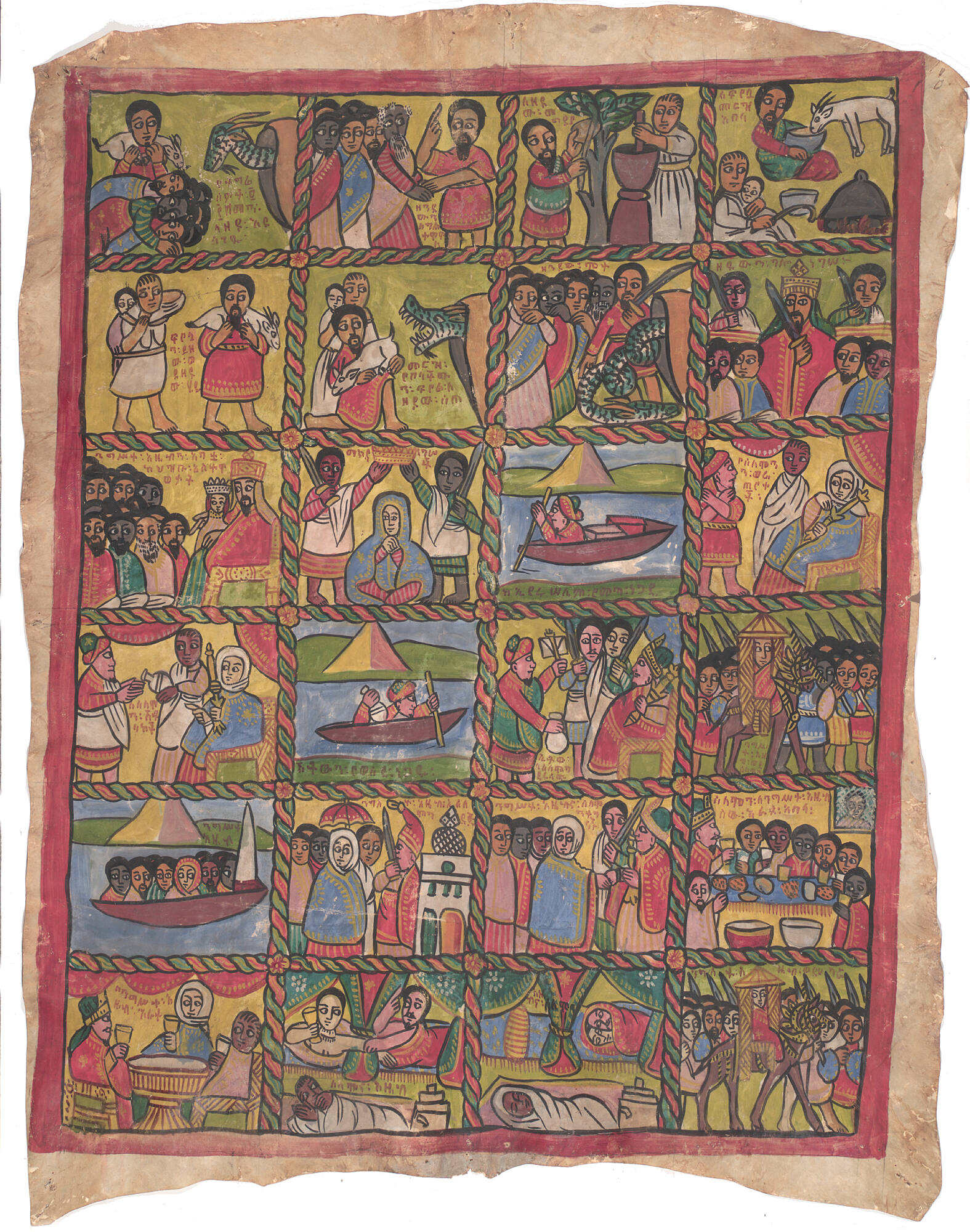

BRIEF DESCRIPTIONThis painting narrates part of the legend of the Queen of Sheba (also known as Make(…)

BRIEF DESCRIPTIONThis painting narrates part of the legend of the Queen of Sheba (also known as Makeda) and King Solomon of Israel.WHERE WAS IT MADE?This painting comes from Ethiopia.HOW WAS IT MADE?The painting was done on animal skin, a common painting surface in Ethiopian traditional art. To prepare the skin, it is cleaned, soaked in water for a few days, stretched over a wooden frame and then dried in the sun. Any remaining meat is scraped away and the inner side of the skin is burnished with a lava stone until it is polished enough to be used as parchment.HOW WAS IT USED?This painting would have likely been displayed in someone’s home. It serves as a visual representation of the oral and written story of the Queen of Sheba. WHO WAS THE QUEEN OF SHEBA?The Queen of Sheba refers (in Ethiopian history, the Hebrew Bible, the New Testament, and the Qur’an) to the woman who was the ruler of the ancient kingdom of Sheba. The location of the historical kingdom may have included both Ethiopia and Yemen. Known to the Ethiopian people as Makeda, this queen has been called a variety of names by different peoples in different times. To King Solomon of Israel she was the Queen of Sheba. In Islamic tradition she was Bilqis. The Roman historian Josephus calls her, Nicaula. She is thought to have lived in the 10th century BC.WHY DOES IT LOOK LIKE THIS?The painting reads from left to right, top to bottom. It depicts a portion of the religious epic recounted in the Kebre Nagast (The Book of the Glory of the Kings). The Kebre Nagast relates the story of Ethiopian Judaism and its transition to Christianity with emphasis on the story of the Queen of Sheba. Although the epic tale begins with the Queen of Sheba’s visit to Jerusalem to meet the famed King Solomon, this painting begins earlier, with a depiction of how the Queen’s father, Angabo, from the land of the Sabeans (east of the Red Sea), came to Ethiopia, a land devastated by the serpent Wainaba. Angabo killed the serpent by feeding it a poisoned goat and was made the king of Ethiopia for freeing its people from years of suffering and devastation. Angabo was then succeeded by his daughter Makeda, the Queen of Sheba).During Makeda’s reign, she heard of the wisdom of King Solomon from an Ethiopian merchant, Tamrin, who had traveled to Jerusalem and met the King. The King had tasked Tamrin to return to Ethiopia and tell the Queen about his wisdom in order to spread the word of God. The Queen then traveled to Jerusalem to meet the wise King. She brought him many gifts and feasted with him, asking him many questions to test his wisdom. Upon returning to Ethiopia, she bore his son, Menelik I, who began the Solomonic Dynasty and carried the title negusa negast, King of Kings, a title that remained in the royal lineage until Haile Selassie, the last emperor of Ethiopia, was deposed in 1974.Narrative paintings that depict this story typically contain forty-four illustrations; however, with twenty-four images, this painting depicts approximately half of the complete story. The legend continues with Menelik I’s travels to Jerusalem to meet his father, King Solomon. After spending some time with his father, Menelik I wished to return to his mother’s kingdom. The King, saddened at the thought of seeing his first-born son depart, prepared a copy of the Ark of the Covenant and ordered his councilmen’s first-born sons to travel with Menelik I and establish a new house of God in Ethiopia. These young men, upset with the King for forcing them to leave Jerusalem, secretly stole the true Ark of the Covenant and took it with them to Ethiopia. The Ethiopian Orthodox Church in Aksum claims to still possess the true Ark of the Covenant. This legend of the Queen of Sheba is central to the construction of national, cultural and religious identity in Ethiopia. Paintings depicting this story, along with representations of the Virgin Mary and Emperor Haile Selassie, can be found in most Ethiopian homes today. – Julia Kim Werts, PhD, History of Art and Archaeology, Class of 2008