Object Details

Artist

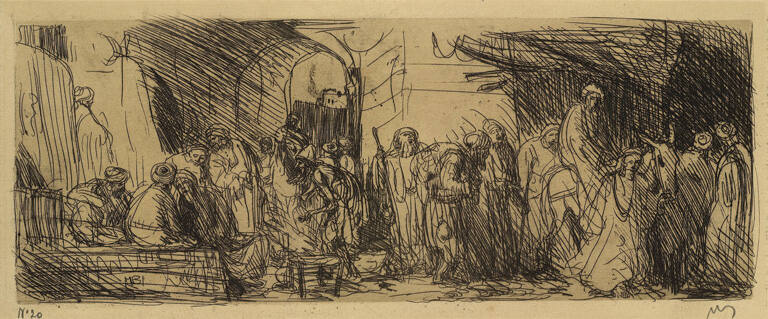

Maxime Lalanne

Date

1884

Medium

Etching

Dimensions

Plate: 7 7/8 × 10 1/16 inches (20 × 25.6 cm)

Sheet: 9 5/16 × 12 11/16 inches (23.7 × 32.2 cm)

Credit Line

Bequest of William P. Chapman, Jr., Class of 1895

Object

Number

62.0172

Vedutisti had long portrayed the building and rebuilding of urban sites, often linking their views o(…)

Vedutisti had long portrayed the building and rebuilding of urban sites, often linking their views of important new construction to the modernization of the city. By the late eighteenth century, Hubert Robert and others would develop the theme of demolition as an aspect of the modernization project. It was a theme with somewhat more ambiguous meanings, resonant with Romantic notions of the unstable and transitory character of human achievement. Lalanne found ample opportunity to extend this theme in Haussmann’s Paris, and here depicts the massiveness of both the destruction and the rebuilding of the French capital in the middle years of the nineteenth century. Like his eccentric contemporary, Charles Meryon, Lalanne brought the traditional medium of etching to bear on his visions of the city. In a sense, Lalanne’s progressive states of this etching are analogous to the different “versions” of Haussmann’s Paris as it proceeded toward completion. In his view of the Boulevard St. Germain in process, a fenced-off construction zone confronts the viewer, surrounded by houses in various stages of demolition; the house at right is, incredibly, still inhabited. The dome of the Panthéon rises in the distance, to the south. This building, too, is a symbol of changing Paris; begun by Louis XV as a church dedicated to Saint Genevieve, it was converted during the Revolution to a secular mausoleum for the remains of great French citizens. The resonance of such an image with Piranesi’s views of Rome is unavoidable, in the tumbled stones in the foreground and the disparity of their scale with the small human presence. The difference, of course, is that the destruction is not one wreaked by time and nature, but by humans. And, as with Baldus’s photograph of the Place Saint-Germain l’Auxerrois, some viewers undoubtedly would have made associations with the relatively recent Revolution of 1848, during which the barricades of insurgents made of these same neighborhoods a landscape of tumbled stone. Decades later, in 1884, in an etching of the Boulevard Montmartre, Lalanne shows one of Haussmann’s masterworks completed and seasoned with time; the uncertainty of tearing down the old is gone, replaced by a straight, tree-lined avenue of uniform facades, sunlit and bustling with pedestrian and carriage traffic.

(Andrew C. Weislogel, “Mirror of the City: The Printed View in Italy and Beyond, 1450–1940,” catalogue accompanying an exhibition organized by the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, curated by Andrew C. Weislogel and Stuart M. Blumin, and presented at the Johnson Museum August 11–December 23, 2012)