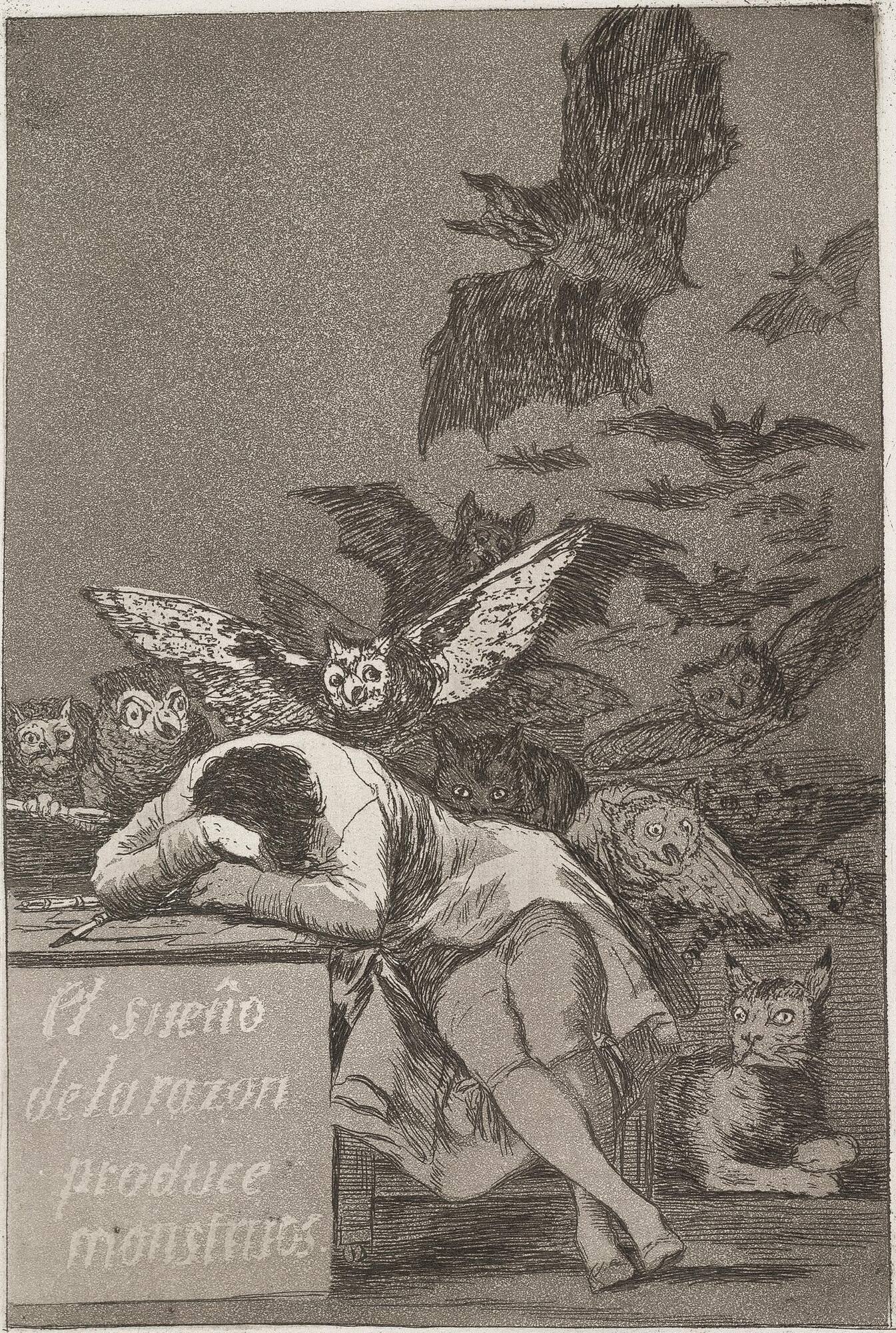

Francisco José de Goya

El sueño de la razon produce monstruos (The sleep of reason produces monsters), plate 43 of “Los Caprichos”

Object Details

Artist

Francisco José de Goya

Date

ca. 1797

Medium

Etching and aquatint

Dimensions

Image: 7 1/8 × 4 13/16 inches (18.1 × 12.2 cm)

Plate: 8 7/16 × 6 inches (21.4 × 15.2 cm)

Credit Line

Acquired through the Museum Membership Fund

Object

Number

63.108

Goya’s Los Caprichos is perhaps the most powerful indictment of a society riddled with human hypoc(…)

Goya’s Los Caprichos is perhaps the most powerful indictment of a society riddled with human hypocrisy and corruption ever produced in prints. The Sleep of Reason, a metaphorical self-portrait, was originally intended to be the series’ frontispiece but, given its evocation of Enlightenment ideas then unpopular in Madrid, Goya chose to position it later in the series. Although he published the first edition of Los Caprichos in 1799, the prints were only on view for a few days when the artist pulled them, fearing the powerful forces of the Inquisition. In 1803 Goya turned the plates over to the King Carlos IV’s Royal Printing Establishment, the Calcographia. They were printed again in many editions after Goya’s death and the installation of a new regime.The Johnson Museum holds a full set of Goya’s eighty prints for Los Caprichos, which provide a rich history of the artist’s sensitivities to the pressing social and economic problems under the leadership of King Carlos IV. In this print series Goya asks, “What happens when reason is absent?”—a question just as relevant today. (“Highlights from the Collection: 45 Years at the Johnson,” curated by Stephanie Wiles and presented at the Johnson Museum January 27–July 22, 2018)The series Los Caprichos is probably Goya’s best known. Comprising eighty plates, Goya privately published the series, which was first advertised for sale in the Spanish newspaper Diario de Madrid in 1799 as being a criticism of “human errors and vices,” although the subjects are often obscure and interpretation purposely difficult. Lampooning both political and religious figures, Goya soon found it diplomatic to present the original plates to the king for his Calcografia, in exchange for a pension for his son. The Sleep of Reason is a self-portrait of the artist, surrounded by demonic-looking animals. It was intended as the frontispiece for the series, but Goya soon thought better of this, probably because the subject related too closely to two plates in Rousseau’s 1793 Paris edition of Philosophie at a time when the very name of Rousseau was anathema to religious and political leaders in Spain. Instead, Goya created another, more traditional, self-portrait as the frontispiece and buried The Sleep of Reason well within the series, as plate 43. In Los Caprichos Goya begins to push the boundaries of the intaglio process to achieve a sense of ambiguous space coupled with a modernist sensibility. This series grew out of Goya’s developing sense of isolation, the result of a protracted illness he suffered in 1792Ð93, leaving him totally deaf. This, along with his difficult position as court painter to King Carlos IV at a time when he was becoming increasingly dedicated to the cause of the Spanish peasants, left him feeling compromised. Relying on a variety of influences, Los Caprichos served as a coded expression of the artist’s growing involvement in Madrid’s political milieu. (From “A Handbook of the Collection: Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art,” 1998)