In the Class of 1953 Gallery, Floor 2L

The Yorùbá word egúngún may be translated as “supernatural powers concealed.” As such, “egúngún” may refer to an ancestral spirit who has temporarily returned to earth to bestow their blessings upon the living or to their lavish, eye-catching regalia.

According to the Yorùbá religious worldview, our ancestors have the power to intervene in our daily lives, for good or ill. Despite the influence of Christianity and Islam, many Yorùbá-speaking communities enthusiastically invoke the presence and blessings of family ancestors at local annual festivals, when dozens of egúngún emerge from their shrines to join the community in spectacular celebrations of music, poetry, song, and dance. The physical manifestation on earth of an egúngún is made possible by male members of the Egúngún ritual association who, aided by training and specialized ritual, are understood to transform into the incarnated spirit of an ancestor when clothed in egúngún regalia.

The egúngún in the Johnson Museum’s collection is of the paka type, which consists of multiple layers of cloth attached to a horizontal beam that rests on the head of the individual wearing the regalia.

An egúngún’s layered panels are designed to be seen in motion: as an egúngún dances through the streets, the multicolored panels of its regalia swirl outward to create a dazzling spectacle that suggests the presence of an otherworldly entity. A tactile model in the exhibition demonstrates the dynamic movement of the dance, creating a “breeze of blessing.”

(Photo: David O. Brown)

Creating an egúngún is an expensive and secret process, requiring the collaboration of a Yorùbá babaláwo (priest), the individual instructed by the priest to commission the egúngún, the chief of the local Egúngún ritual association, the herbalist who prepares the egúngún’s protective medicines, and the tailor who assembles and sews the regalia.

Elaborate dress and luxury fabrics signal social power in Yorùbá society. Choice materials for an egúngún’s regalia typically combine machine-made, imported fabrics, such as velvet and Dutch wax cloth, with costly, locally handwoven indigo-dyed cloth; it may be additionally empowered with objects like cowrie shells that were used as currency. A touch table in the exhibition displays a range of different materials that might make up an egúngún.

(Photo: David O. Brown)

In 2023, Johnson Museum staff, along with guest conservators Lisa Goldberg and Gwen Spicer, engaged the diaspora-based ritual and spiritual expertise of Babaláwo Oluwole A. Ifakunle Adetutu Alagbede, a babaláwo (Yorùbá priest) and scholar based in Harlem.

Babaláwo Alagbede instructed us in ritual protocol regarding appropriate forms of greeting, feeding, housing, and handling the sacred regalia in the Museum’s care.

As a result of our consultation, we revised our approach to caring for and displaying the egúngún, which included proximity to water and a softly lit gallery.

(Photo: William J. Woodams)

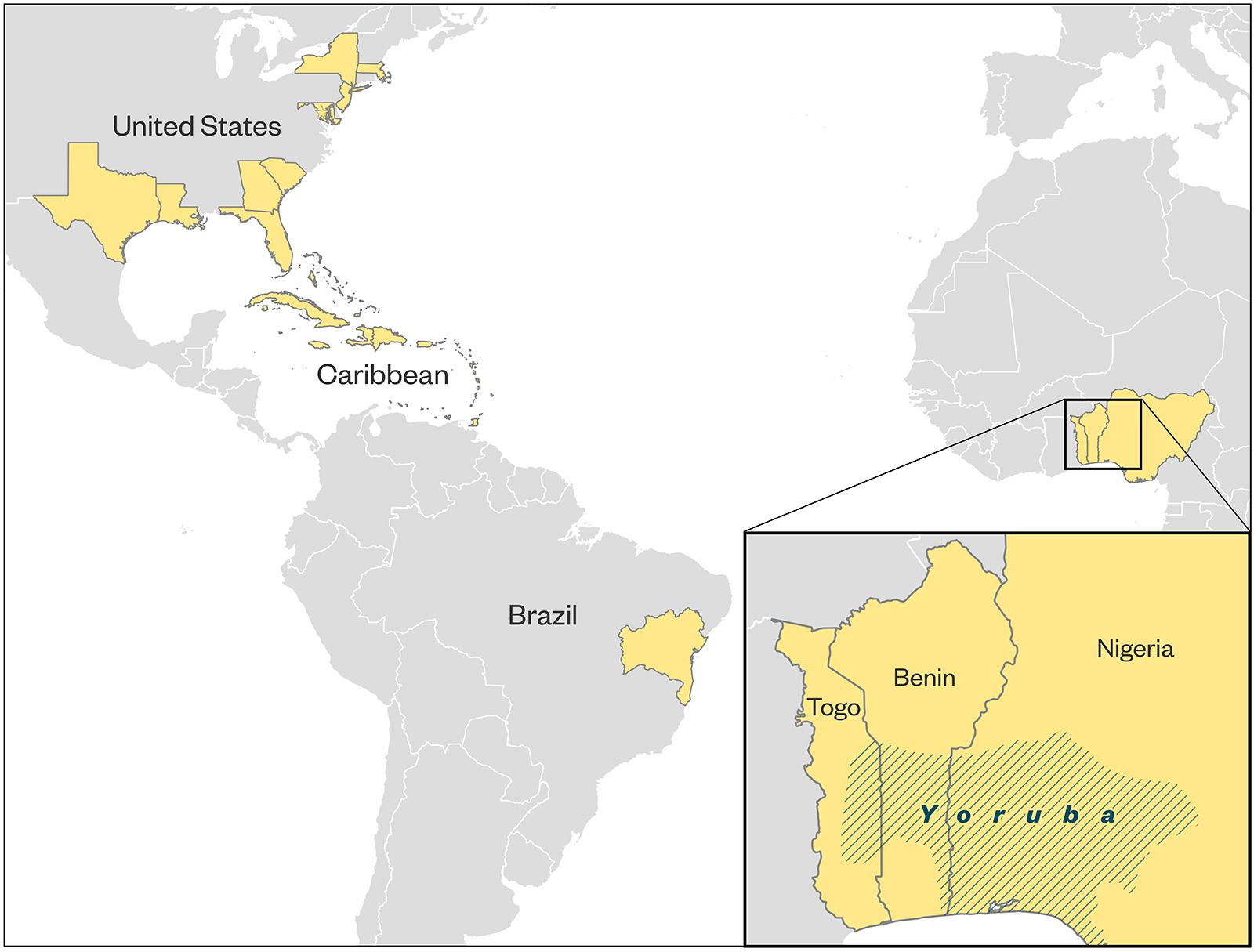

While its origins are centered in the West African nations of Nigeria, Benin, and Togo, Yorùbá religious culture may be found in all corners of the world, with notable concentrations in Brazil and the Caribbean as a consequence of the Atlantic slave trade. Beginning in the 1960s, New York City became a prominent center with the advent of Black American Yorùbá revivalism. Closely aligned with Black Nationalism, this movement aimed to nurture African religious practice amongst Black Americans looking to connect with their African roots.

(Map designed by Keith Jenkins, GIS & Geospatial Applications Librarian, Cornell University Library)

This exhibition was curated by Gemma Rodrigues, Curator of the Global Arts of Africa and Ames Director of Education, and Grace Okine, PhD Candidate in the Department of History, and supported by the Ames Exhibition Endowment. Our special thanks to Andrea Murray, Lead Educator and Pre-K–12 Curriculum Development Specialist; Associate Professor Rebeca Hey-Colón; Dr. Kehinde Adepegba, Lagos State University of Science and Technology; and Oluwole Akinniyi for their generous collaboration. Conservation of the egúngún was made possible by Susan E. Lynch.