Object Details

Culture

Lambayeque (Peru)

Late Intermediate period

Date

ca. 1000–1350

Medium

Cotton, or cotton and camelid wool

Dimensions

38 1/2 × 17 3/4 inches (97.8 × 45.1 cm)

Credit Line

Bequest of Michael A. McCarthy, Class of 1956

Object

Number

2002.123

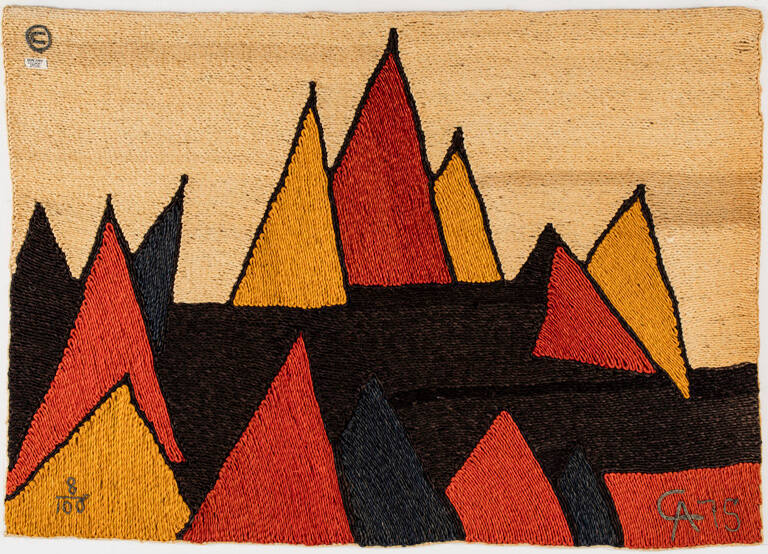

BRIEF DESCRIPTIONThis large slit-woven Lambayeque tapestry panel has been cut apart from a larger ga(…)

BRIEF DESCRIPTIONThis large slit-woven Lambayeque tapestry panel has been cut apart from a larger garment, probably a tunic.WHERE WAS IT MADE?This tunic panel was made in the coastal area of what is now Peru. We know this because—although tapestries have been found in burials at some distance from their points of origin—tapestries woven in coastal regions were made using a technique that left vertical slits between different sections of color. This particular tapestry fragment has such slits. Although we do not know the exact provenance of the piece (where it was found) it was likely found along the coast, since the dry climate helped preserve buried textiles that would have otherwise decomposed in more humid regions.HOW WAS IT MADE?This panel was one of a number of panels that were woven separately and then stitched together to form a full garment; the bottom and the left edge of this panel appear to be edges of the original garment. Even this panel itself is made from smaller panels and strips of woven cloth.This textile is probably made from two kinds of fibers: cotton and camelid wool (from llamas, alpacas or vicunas). In coastal textiles, cotton usually served as the warp (the vertical threads of the weaving) and was left undyed. Camelid fibers, which are better at absorbing colors from dyes and more resistant to fading, were often used as the weft threads. Weft threads are woven in between the warp threads, and in Andean textiles are generally the only visible threads. Dyes were made from a variety of natural materials. Bright red came from the cochineal insect, while yellow colors came from a wide range of plants including pepper tree seeds. Blues were obtained from the indigo plant.Coastal textiles were mainly woven on small backstrap looms. The loose unwoven end of the warp threads is attached to a stake in the ground while the woven section is secured around the weaver’s waist, stretching the long warp yarns taut. The weaver must pull hard on the stick with loops around every other warp yarn (“heddles”) in order to open a space between the odd and even sets of yarns. The opening created is called the “shed.” The horizontal weft yarn goes through the open shed, then the second stick with the other warp yarns is lifted, and the weft yarn passed back through in the other direction.HOW WAS IT USED?Textiles were generally used as garments. We know that textiles were highly valued commodities during the Inca period, used to bind contracts, pay a form of tax, and given as gifts. They were likely used for trade by many earlier cultural groups, as textiles made in one area have been found in burials in other, distant regions.WHY DOES IT LOOK LIKE THIS?Notice the four large figures, one in each quadrant of the panel. They may represent Naymlap, the mythical founder of the Sicán culture in Lambayeque. Naymlap is said to have arrived over the sea with his wife and 40 retainers. These Naymlap figures are depicted in the manner of “staff god” images associated with agricultural fertility; the figures hold elaborate objects in both hands. The figures wear elaborate tunics and crescent-shaped headdresses from which two tiers of large, cascading plumes emerge. Large, crescent-shaped headdresses of this sort are common on north coast textiles of this period.The figures are bordered at the top and bottom by rows of stylized feline faces. Between the rows of feline faces are a series of pyramidal stepped figures with anthropomorphic heads wearing headdresses appearing to be smaller versions of those worn by the larger figures. These stepped figures may represent mummy bundles, which are often roughly pyramidal in shape and are sometimes surmounted by masks and headpieces.