Object Details

Culture

Chimu (Peru)

Date

1000–1470

Medium

Cotton or camelid wool on cotton

Dimensions

9 1/2 x 11 1/2 inches (24.1 x 29.2 cm)

Credit Line

Gift of Joan Barist, Class of 1963

Object

Number

94.002

BRIEF DESCRIPTIONThis is a Chimú textile panel featuring an animal referred to as a “moon dragon.(…)

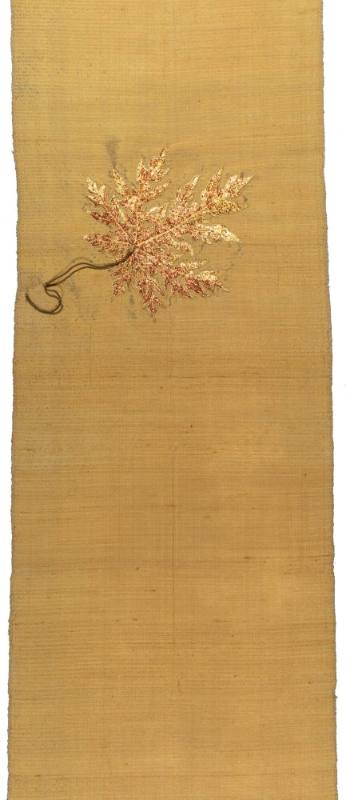

BRIEF DESCRIPTIONThis is a Chimú textile panel featuring an animal referred to as a “moon dragon.”WHERE WAS IT MADE?This was likely made in the coastal region of what is now Peru. We know this because, although tapestries have been found in burials at some distance from their points of origin, tapestries woven in coastal regions were made using a technique that left vertical slits between different sections of color. This particular tapestry fragment has such slits. Although we do not know the exact provenance of the piece (where it was found) it was likely found in the coastal area as well, since the dry climate helped preserve textiles in burials that would have otherwise decomposed in more humid regions.HOW WAS IT MADE?This textile is made from two kinds of fibers, cotton and camelid wool (from llamas, alpacas or vicunas). In coastal textiles, cotton usually served as the warp, the vertical threads of the weaving, and was left undyed. Camelid fibers, which are better at absorbing colors from dyes and more resistant to fading, were often used as the weft threads. Weft threads are woven in between the warp threads, and in Andean textiles are generally the only visible threads. Dyes were made from a variety of natural materials. Bright red came from the cochineal insect, while yellow colors came from a wide range of plants including pepper tree seeds. Blues were obtained from the indigo plant.Coastal textiles were mainly woven on small backstrap looms. The loose unwoven end of the warp threads is attached to a stake in the ground while the woven section is secured around the weaver’s waist, stretching the long warp yarns taut. The weaver must pull hard on the stick with loops around every other warp yarn (“heddles”) in order to open a space between the odd and even sets of yarns. The opening created is called the “shed.” The horizontal weft yarn goes through the open shed, then the second stick with the other warp yarns is lifted, and the weft yarn passed back through in the other direction.HOW WAS IT USED?Although this small panel is complete (the edges are woven, not cut), it was once originally stitched to other woven panels to form a larger piece. Textiles were generally used as garments. We know that textiles were highly valued commodities during the Inca period, used to bind contracts, pay a form of tax, and given as gifts. They were likely used for trade by many earlier cultural groups, as textiles made in one area have been found in burials in other, distant regions.WHY DOES IT LOOK LIKE THIS?This panel depicts a mythical animal referred to as a “moon dragon.” Similar animals are represented in artwork by other pre-Columbian cultures. To see an example on a Manteño stamp seal in the Johnson Museum’s collection, search for object number 2006.070.287 in the keyword search box.Notice the triangular spikes along its back, and the crested headdress above its head. This headdress is seen in artwork from other cultures of the Andes. Although stylized, this creature appears to retain elements from the pampas cat, a small wildcat, such as the combination of spots and stripes, and the spiky back (a feature of a defensive pampas cat.)ABOUT THE CHIMÚ CULTURE:The Chimú Empire, or Kingdom of Chimor, was established in the Tenth Century in the Moche Valley on the north coast of present-day Peru. By 1400 AD, the Chimú ruled an empire 800 miles long, encompassing the fertile, agriculturally productive irrigated coastal valleys stretching from Tumbez to Chillón. The imperial capital of Chan Chan, located near the modern city of Trujillo, covered 20 square kilometers, housed a population of 50,000 to 100,000 people, and included pyramids, residences, markets, workshops, reservoirs, storehouses, gardens, and cemeteries. Chimú architecture is made of adobe decorated with geometrically patterned mosaics or molded bas-reliefs of stylized animals, birds, and mythological figures. Chimú artisans used similar decorative elements in their pottery, metal ornaments, and finely detailed textiles, many of which are embellished with ornate featherwork. Chimú pottery was mass-produced in molds by craft specialists and is typically highly burnished blackware. The most common shape was the stirrup-spout bottle, which often has a small monkey figure located on the spout. After the Inca conquest of Chimor in 1470, during the reign of Pachacutec Inca Yupanqui, Chimú vessels tend to have broad, flaring spouts similar to those on Inca aryballoid jars. Chimú-Inca vessels often have shapes similar to the Inca aryballos or urpu, but are made of typically Chimú blackware and are decorated in characteristically Chimú style.