Agostino Brunias crafted popular pictures for elite European audiences before joining the British colonial administration in 1770 to document life on the Caribbean island of Dominica.

Tasked with depicting the newly acquired colony for British subjects on both sides of the Atlantic, Brunias produced views that play up its exoticism and natural bounty.

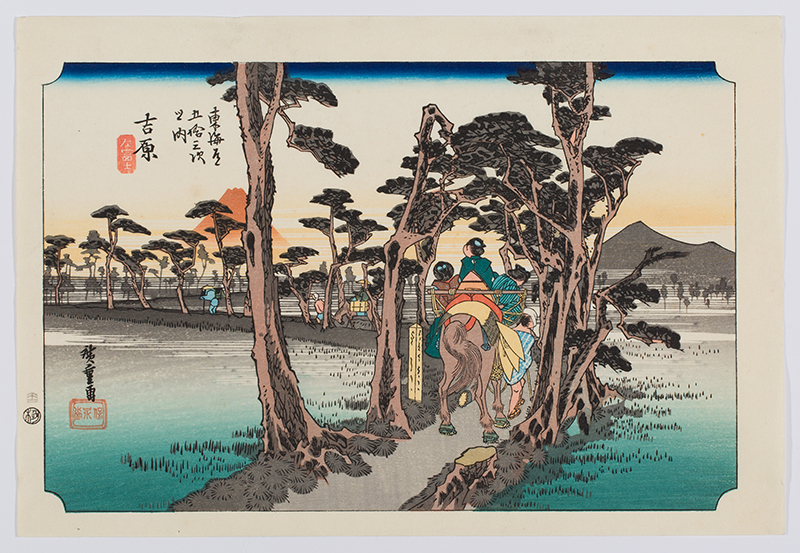

Brunias’s official role suggests that this work must be an accurate observation of life on Dominica. However, he combined his sketches from life with established artistic genres to construct idealized scenes. Here, a stream provides a pretense to gather a spectrum of Dominica’s inhabitants. Brunias renders costume, skin color, and activities with ethnographic specificity. Each of his figure studies provides the viewer with cues about group identity and social status—the strolling landowners recall popular portraits of English gentry outdoors, while the women washing clothes bring to mind sentimental paintings of the working class. These types would have been familiar to Brunias’s audiences, allowing him to communicate the complicated social, class, and racial structures resulting from colonization on Dominica within a painting that reads as an attractive scene of leisure and labor.

—Leah Sweet, former Lynch Curatorial Coordinator for Academic Programs at the Johnson Museum

Sugar and Agriculture

Agriculturally, Brunias’s View of Roseau Valley shows the availability of four important components for successful farming: land, water, labor, and a tropical environment. To the left, land has been cleared for cropping, though the actual crop is not easy to identify. There is plenty of water flowing from the hills indicating sufficient rainfall, even for irrigation or watering in dry spells. Agricultural labor is not depicted, yet the fields beyond the river are harvested and the houses have thatched roofs made with straw from the crop. Domestic work such as washing clothes, gathering wood, and carrying heavy items also suggests an available work force. There seems to be no animosity toward the probable landowners strolling on the right. The peaceful scene only hints at the major land development that occurred on Dominica during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries with indigenous, imported, and slave labor.

British Dominica was known in the eighteenth century for its sugarcane plantations, many of which were financed by absentee landowners in England. These estates populated the island’s coastal lowlands, whose productivity and availability are highlighted in this painting. In contrast, the lush, mountainous interior of the island in the background appears uncultivated, though it was and remains an important site for farming tree crops such as coffee due to its cooler climate. This omission likely stems from British economic and agricultural focus on sugarcane as an export crop in the mid- to late eighteenth century.

—Peter Hobbs, adjunct professor / associate director, IP-CALS academic program, School of Integrative Plant Science, Soil and Crop Sciences Section, Cornell University

Imperial Social Engineering

Imagine a part of the world where and when European imperial sovereignties could cast themselves across the Atlantic Ocean because of their unprecedented utopian and, at the same time, violent experiments with human labor. Besides having to “invent” the region theologically, intellectually, politically, and artistically because neither it nor its indigenous inhabitants existed in the Scriptures, what turned the islands into utopian experiments were accounts, such as Columbus’s, in which he depicted the archipelago as a bountiful new Eden, replete with familiar and strange resources and docile souls. It was not coincidental that later in Utopia (1516), Thomas More imagined his ideal society as an island that could be hewn from rock. Nor did Shakespeare miss the mark in his representation of the relations of power between masters, servants, and local slaves on an island in The Tempest (1611). By the eighteenth century, Caribbean sugar production, as C. L . R. James demonstrates in The Black Jacobins (1938), provided western Europe with room for its most advanced technologies and most widespread use of indigenous, slave, and indentured labor.

When I closely examine Brunias’s View of Roseau Valley, I consider the unlikely composite and staged nature of the landscape and its posed characters a fitting depiction of the power and wherewithal of European empires to invent and experiment with Dominica’s island society. The vegetation is both European and Caribbean, and the people, as in fictions of pure species, apparently unmixed. Brunias’s painting is both an erroneous depiction of the natural world and an appropriate rendering of imperial social engineering.

—Gerard Aching, Professor of Africana and Romance Studies (retired), Cornell University

Violence: Gendered and Raced

View of Roseau Valley might be viewed alongside the most visible literary portrayal of Caribbean slavery in eighteenth-century England, Aphra Behn’s novella Oroonoko (1688) and its subsequent theatrical redactions. Behn’s and Brunias’s visions are connected in two ways: both feature a female centerpiece; and Oroonoko places into fluid contact the indigenous Carib population, the African slave, and the British planters, just as the painting provides the viewer with a similarly shifting landscape of racial identities.

Behn’s narrative version of this scenario might then offer suggestions for an interpretation of Brunias’s vision. The central female figure of Oroonoko—the beautiful, doomed Imoinda—seems momentarily to resolve the dispersed identities of the novella, as her beauty transcends race and slavery. In the same way, Brunias’s bright, central female figure holds together the very fair-skinned Creole planters on the one side, her stature and whiteness gathering and balancing theirs, and the laboring, kneeling, washing African and Carib population that she emerges from on the other, since she is burdened as a laborer by the basket on her head.

Yet in Oroonoko violence is the implicit and unavoidable necessity of Imoinda’s perfection. For the reader of Oroonoko, then, the key question for Brunias might be about the violence lurking within this engagement with colonial gender and racial identity: Where is that violence concealed? When does it emerge? How does it taint the pleasant pastimes represented in the valley?

—Laura Schaefer Brown, John Wendell Anderson Professor of English, Cornell University

Textiles and Trade

Brunias depicts an amalgam of dress standards as modeled, shared, or imposed by French and English colonial plantation owners and adapted by various wearers. It is challenging to see this painting as a specific visual report, as the artist recycled figures and poses from one picture to another. However, the painstakingly detailed costumes not only help construct an artificial scene meant to edify and entice British audiences, they capture the very real demand on the island for finished goods such as cloth due to colonial mercantilism.

Dominica’s colonial inhabitants in the eighteenth century, whether free or enslaved, elite or humble, depended on imported textiles to dress. Some were manufactured in France or Britain, who battled for control of the island during this period, while others were imported goods from colonial markets in India and Africa. The British were the most successful in merchandising their own cottons, linens, wools, and silks around the “Atlantic rim,” but both empires had a vested interest in selling national manufactures to their colonies.

The emphatic display of red and blue textiles in this painting similarly raises the question of visible fact or fiction. Brunias gives particular attention to skirts and kerchiefs with red and blue borders or stripes, as well as a bright red parasol, which would have been an unusual sight in Europe. Though this repetition may serve to aesthetically and symbolically unify the figures into one composition, Turkey red and indigo blue were in fact common dyed colors of the day, favored for their beauty and resistance to fading in sunlight and laundering.

—Susan Greene, MA 1994, American Costume Studies, Fiber Science & Apparel Design, Cornell University / independent scholar